26 November, 2010

Twice last week I thought I had died and gone to Flamenco Heaven, but each morning woke up with a well-deserved hang-over in decrepit and depressing Berkeley.

That is perhaps as it should be, and not just the hang-over. I spent the early summers of 2003 and 2004 in Andalusia first in a Spanish immersion and then studying flamenco guitar, so I am well aware that, say, Jerez de la Frontera is also decrepit and depressing, as are similar venues in southern Spain: Sevilla, Cádiz and Morón de la Frontera, whose passionate, mocking, exultant style of flamenco was on display in last week’s show, Flamenco Gitano.

In fact, it might just be that transcendental art – I use the words advisedly – must be rooted in depression, or at the least a deep sense of the vulnerability and sordidness, the hopelessness and delusional obsessiveness of human existence, else there be no grounds for transcendence. I realize that such an esthetic framework will not win many adherents in the cheery materialistic world in which we live, meliorist and ameliorist at once.

It was by no accident that the shows were extraordinarily successful, the audience in tune with almost every move and change, this in the view of the troop itself, who gathered afterwards with those who could at a local restaurant-bar, La Rose Bistrot on Shattuck, to share food and wine, which was exactly how things should be.

For two generations there has been an active flamenco community in the Bay Area, as odd as that might seem. Among the then exotic destinations many early boomers set themselves was Andalusia. Some of these gypsies, so to speak, spent time in the pueblos south-east of Seville and were entranced by flamenco. Those who gravitated to the Bay Area were joined by emigrants and exiles from Spain and Latin America, forming a small but now greying community of aficíonados to which I belonged in the 1980s and with which I am now reconnecting.

For years there were weekly flamenco shows at the Old Spaghetti Factory in North Beach – I attended the last one in 1984. There are still a surprising number of talented amateurs and semi-pros, plus an informed public, flamencos who are not necessarily themselves performers but who are, to borrow the words of Donn Pohren, emotionally involved in this “unique philosophy” – a way of life.

North Beach Old Spaghetti Factory – I don’t remember ever seeing it this clean

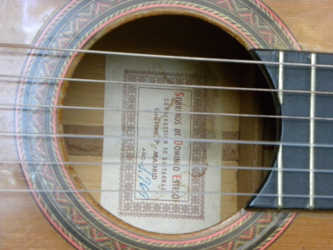

More to the point of my trip last week, there are enough flamenco guitarists in the Bay Area to comprise a market for one of my guitars, a 1969 Sobrinos de Domingo Esteso.

Last summer I decided to pass this wonderful instrument on to others, having played it since 1984 when I bought it from my friend Keni, known in the milieu as Keni el Lebrijano. Keni is an example of the aficíonados described above. He spent time in village of Lebrija, about 30 km north of Jerez, also studying in Morón with the great Diego del Gastor. He has performed with the likes of Agujetas, memorably for me at a three day juerga in Big Sur in 1985, of which I still have a cassette recorded live on my now antiquated Walkman WM-D6 Pro. (Memo to self: digitalize that tape!)

Twenty-five years later Keni offered to broker the Esteso, in some way closing a sacred circle. This is fundamentally the right thing for me to do. The guitar has years on it and deserves to finish out its days where flamenco is lived, not in my sterile little study in the coastal hills of Orange County. Moreover, I had if not a facsimile at least an approximate copy made by my luthier friend Markus Kirchmayr in Innsbruck. Here is the interior bracing of the Esteso as Mark copied it. It is not the same guitar, to be sure, but has its own charms. I shall probably play it until I die.

What I love about the Bay Area is its variegation. I like to imagine this proceeds from the original human inhabitants, though it actually came through them, since it is rooted in the complex eco-system of the area, the juxtaposition of biological niches, disparate weather and climate zones –fog here but not there, winds, currents and tides ever-shifting, as those of us who have sailed on the Bay know, objective reminders that stability and permanence are utter illusion. Buddhism is the default religion.

There is another quality which attracts me and I share. Scratch the surface of a denizen and, bit by bit, a coherent, internally consistent but often conspiratorial or paranoid view of the world will unfold and deploy. True enough, self-help and therapy are constant themes, reflecting an American especially Californian a/meliorism. But, overall, this is a Lucretian milieu in which, further to mix and mash the metaphor, monads pulse around without interacting until a chance bump sparks a flash of communication, a shock of mutual recognition, a moment in which we Berkeley monads surprisingly transcend our selves. When we start talking it is more a hallucinatory style of thinking we share rather than any specific content. Somehow those styles themselves connect.

Don’t ask me to explain in detail but this mode of thought and feeling is related to gypsy flamenco.

During the post-performance fiesta at La Rose Bistrot, copious quantities of wine were flowing. Out on the sidewalks tokes were exchanged among greybeards and young alike, though we were all already high on the flamenco and the collective rapture it had produced. Yes, even cigarettes were smoked.

In the general hurly-burly around the bar, I ran into various old friends and made new ones, including a woman my age who had been in Morón in her youth, and Berkeley since then. All day, as I nursed my hang-over from the first night’s fiesta, I had been contemplating the misery and splendor of Berkeley, so I asked her how she had managed to live out her life there, how, that is, she personally surmounted the despondency and craziness and desperation the place fosters. She knew immediately what I was talking about.

“Yes,” she said, “there are moments when you start thinking you need to find a way out, though preferably not a hand-gun. But there are sooner or later and sometimes just in time redemptive moments when you realize something miraculous is happening to you and that it could only happen in Berkeley.”

Despite everything, Berkeley offers fertile ground for fortuitous miracle. It was an ideal venue for flamenco, better even than sometimes in Spain, where the general public doesn’t give a rat’s ass for this music, or anything associated with gypsies.

Last week enough of us were there who do give a rat’s ass for Flamenco Heaven to descend.

***

A search on the internet will give some idea of what this guitar is worth, but also of the complex question of authenticity of guitars made by or attributed to the Conde family. This is a question I was not and am still not concerned with, since I am not a collector of anything, not even of wines when I was a wine merchant and had access to some of the best in the world.

A guitar is worth what it sounds like it does to you. And like any item, its price is a factor of how much money you have to hand.