Follow the slightly revised but mostly simply transcribed diary notes from the overland trip myself and two friends, Louie Nosko and Tom Lane, took in January, 1968, from Bamako to Timbuktu, Niamey, Ouagadougou and Abidjan, eventually back to Liberia, where we were teaching at Cuttington College.

It is unsettling to come upon ones own words at this remove. Readers may or may not share the embarrassment, but also the complaisance I feel for this avatar of myself, pompous to be sure, also insecure, sometimes overly earnest – qualities betrayed by and translated into my jejune literary style at that point in time. I was twenty-two.

No question, though, that this was the first great travel adventure of my life. It marked me deeply, inscribing themes and topics which returned decades later ovr my career as Africanist, a significant part of which had to do with representations of Islam in African literatures. I remain proud of having been part of the first serious consideration by Europeans and North Americans of the role of Islam in African literatures in French and English, a movement of which Ken Harrow’s Faces of Islam in African Literature (1991) was a prime example, one might even say prime mover. My piece in it“Through a Prism Darkly: Orientalism in European-Language African Writing”, served as conclusion to it?

A few years later, Ken edited a second book, The Marabout and the Muse: New Approaches to Islam in African Literature, in which my“Jihad, Ijtihad and Other Dialogical Wars in La Mère du printemps, Le Harem politique, and Loin de Médine”. In a age perversely obsessed with Islam, it is worth a read: download it here.

*

12 January, 1968. Robertsfield, Liberia. The Russian turboprop on the ground at Robertsfield was long and sleek and decorated with a single yellow stripe. I was struck by some of the passengers waiting to board, men wearing attractive flowing robes, hats of the Sekou Touré variety, sunglasses of the American Air Force sort. Two women, one large and dressed in a showy multicolored outfit of diaphanous but not transparent material, and another, elegant and statuesque and wearing a dress made out of green lappas with a head tie of the same material. When we got on the plane, the latter turned out to be the hostess. Whenever I glanced away from the window – for I was very interested in watching the progression from rainforest to savanna – it was to follow her swaying movement down the aisle.

Through we were flying for most of the trip too high to see detail, I could detect, after about an hour, increasingly large patches of treeless ground until, as we descended, trees became rare, scribbles on the barren landscape. Just as we landed, there were signs of cultivation, squared-off plots of land, trees organized into thin rectilinear networks. The air, as we stepped out of the plane was hot and dry, but a welcome change from muggy Liberia. We were expecting much palaver, since we had no pre-arranged visa.

We went into customs and got tangled in officialdom until an attractive couple, a slim Malinké girl of delicate features and a tall, equally handsome man, introduced themselves as representatives of the Tourist Office. They took us in hand, showed us where we could change money, insisting we count it after the exchange was given us. Eventually, they led us to the Tourist Office. I may have been influenced by the fact that everything was in French but I was impressed by the friendliness and manners of the men there. We ended up at a small hotel by the train station – Buffet de la Gare – and had time to relax before we took off to find a place to eat.

Driving into Bamako from the airport had been entering a different world than the one we had become accustomed to after six months in Liberia. The streets were narrow, there was less traffic, though bicycles and motorcycles proliferated. The shapes of the buildings, almost all of a single story, were unusual to my eyes. Everywhere Malinké men in their bright blue robes petalled through the streets. Others, especially those involved in officialdom, wore unornamented Mao-suits, or so they appeared. The women were dressed in colorful and elegant yet simple robes, almost always color-coordinated.

The colors of Bamako were very different from Liberia. Even in the dry season Liberia is green, though not necessarily fresh and clean. Bamako, because of the dust which hangs in the air, is pink and brown and made more striking by the contrasting crisp blue Mandingo robes, which proliferate. The mosque near the center of town is pink brick, a large version of the one I knew in Gbarnga, Liberia, the first mosque I had ever seen in my life. Except for this and a few other mosques plus the remnants of French colonialism, there were few large buildings. Yet despite its narrow streets, Bamako seemed spacious, more so than Monrovia, less cluttered with dilapidated shacks.

There was indeed a lot of French about this city but much also African, or what I liked to imagine as African. It was an urban society which was not a product of the West alone. I attributed this to the Marxist government of Modibo Keito [who was to be ousted ten months later].

There were to be sure many more cars in Monrovia, but most are taxis or ostentatious vehicles owned by a few rich purveyors of foreign goods and technology. Those who do have cars have huge ones; those who don’t have one have nothing. In Bamako, on the other hand, a large portion of the population appears to have a bicycle or a motorcycle. One man, who voluntarily picked us up off the streets while we were waiting for a taxi and was evidently a functionary in the government, well-educated, charming, had a small but perfectly adequate French automobile, a Renault of the sort I knew from France. As he drove us through the streets of Bamako after our diner at Les Trois Caïmens (The Three Crocodiles), the restaurant we had found our way to, he chatted about the time he spent in the States.

— Ah oui, j’ai fait New York, j’ai fait Washington, j’ai fait Milwaukee, j’ai fait plusieurs villes américaines.

He had neither the suppressed hostility towards nor fear of whites, nor the overweaning need to impress and prove his worth that one encountered often in Liberia. He was sure of his equality, did not need to insist upon it. He was relaxed and unconcerned with being anything but what he was: an African, a Malian, in the last third of the twentieth century.

In the Trois Caïmens, the waiter’s face had brightened when he answered: oui, ce restaurant appartient à l’État. Tous les grands hôtels et restaurants appartiennent à l’État.

A man at the bar asked me, pointing at my Vai tie-dye shirt: c’est la tenue d’un hippie. A word which it took a double-take for me to recognize.

13 January, 1968. The next morning we went to Sécurité and attempted to get visas. The officials were, as might be expected, confusing and contradictory, but we filled out the forms and I composed a letter to the Director asking for a visa and explaining that we didn’t have any, a formality perhaps, but what seemed to us to be a deliberate obstruction. Then we left.

Two young boys had attached themselves to Tom and Louie and upon my return, they found someone to speak French to. They also thought we were hippies. My shoes, they thought, must have come from San Francisco. Tom was, in their eye, a German.

— Je déteste les Allemands.

— Il ne faut pas dire les choses comme ça.

— Excuse-moi, mais je lance toujours de telles phrases.

— Quels Allemands? Les Allemands de l’Est ou les Allemands de l’Ouest?

— Ceux qu’on connait ici, de l’Est, mais je déteste aussi les Allemands de l’Ouest, ces capitalistes!

At first they were interesting but it became obvious that they had decided to attach themselves to us for good.

— Aimes-tu les acteurs américains?

— Oui, trop!

— Trop? Alors qui aimez-vous?

— Montgomery Cliff. Robert Mitchum. John Wayne.

— John Wayne? Mais ce n’est pas un bon homme.

— Je sais. Il n’aime pas les Noirs.

— Tu as laissé ta femme au Libéria?

— Je n’ai pas de femme.

— Pas de femme? Ça te gênerait d’avoir une fille noire? Des enfants noirs?

— Ça m’est égal. Beaucoup sont très belles.

We ate in a restaurant off the Place de la République. Some plat africain whose name escaped me. Afterwards we took a taxi back to the hotel.

It had become apparent that the occasional whites I saw driving around in small cars and on motorcycles are Russians, and not particularly friendly. One beautiful Russian blond whipped by us on a Vespa. In one section of town, just south of the railroad station, ressembled for two or three streets a French provincial town. People were clustered around the markets buying groceries. The fresh fruit and vegetables are far more abundant than in Liberia and in much better condition.

We stopped at the Artisans’ Building, near the mosque, and glanced at the wares. Tom wanted to buy a crocodile belt and when he was offered one for 3000 francs maliens, he tried to bargain, through me of course. His return offer was far too low, and the merchant turned away from us in what I interpreted to be anger.

At another shop we had an argument with one of the artisans, who insisted that all Americans are rich. I attempted, half-heartedly, to suggest that not all but many were, but he remained totally unconvinced. Yet another warned us that les choses ne sont pas bonnes ici. Il vauderait mieux cacher les portefeuilles — indicating the wallet Tom had sticking out his front pocket.

There was a statue in the Place de la Liberté which celebrates the French Armée noire in the First World War. To it had been attached a small sign which read: Aux sacrifiés du colonialisme, la patrie reconnaissante — To the victims of colonialism, from the Homeland.

There was the Bamako of mud-walled, squat and crumbling slums just south of the mosque, and there was also the Bamako of the old colonial neighborhoods. Large mansions spread out in the area south of the train station, where there was a huge Catholic church. These old buildings have been converted to new purposes. In one, beyond the dry trees of a dusty courtyard, we could see karate practice. One of the boys told me that this was his only sport. Occcasionally a European, sometimes a priest with a long beard and a weird hat, would pedal through the traffic, but in general the cyclists were Malian. They somehow managed to keep their long robes from the uncovered sprockets.

The most distinct odour in this city was not that of refuse and excrement, but of marijuana. Perhaps it was not marijuana, for if as much as we seemed to smell were being smoked, the city would be absolutely still, without movement, lost in a trance. Maybe it is the dust or the burning leaves or the cooking which smells like grass.

Whatever the condition of the neighborhood, whatever style we were surrounded with, colonial decadence or adobe decrepitude, one thing was constant: dust hangs in the air, diffusing the light. The mucus of the nostrils, the inside of the mouth, the fingertips and eyelids were all dry. The streets and the high trees which hang over the empty grassless courtyards were covered with a film of dust.

14 January, 1968. Last night we ate at the Grand Hotel where we had a so-so meal, and I got so-so drunk. I met a Congolese on his way to Moscow when I went after cigarettes. He made some joke in French, to which I replied, but then he was surprised when I admitted I was an American. There was a shift in your relationship when someone discovered you were an American, subtle though it be. You could feel preconceptions and but then curiosity cutting in and out, but sometimes a mild surprise at having exchanged amenities with a harmless and well-meaning white man who has been instantly transformed into a living of example for which there is well-prepared stereotype.

The trains rolled by outside my hotel window, less than twenty yards from my rickety desk. From the two-by-two-yard balcony, I watched people carrying baskets of vegetable and gourdes on their heads, gourds which looked like they were full of milk. They scrambled over the tracks, oblivious to the infrequently passing trains, violet and blue gowns and sheets of cloth furling out in the breeze behind them. With the exception of a few tattered boys en hallions, they were well-dressed. Most of the men wore flowing robes bunched up over their shoulders in the heat of the day, pointed leather slippers which leave the heels bare. On the streets passed the occasional beggar, a leper, a woman wrapped in dirty cloth whose feet were bound with bandages, a man without pupils in his eyes.

In the cafe the next morning, empty except for a few ladies behind the bar, I had coffee and read a few pages of Soundjata, the great national epic of the medieval empire of Mali.

The terrace was also deserted, and the waiter brought my bowl of café au lait in his own good time. On the greenish walls, which bear stains up in the corners the walls meet the ceiling, there were Gauginesque pictures of caramel-skinned bare-breasted women standing before savanna-scapes. A fourth picture was of an old, apparently white woman wrapped in blue cloth with a veil of cloth across her head. No idea what this meant.

The cafe was cool and humid and high-ceilinged and, compared to the glare outside, dark. The floors were of the same red tile which floored my room and the gallery on the second floor of the hotel. You look across and down from the gallery which leads to my room to the concrete patio outside of the cafe. Beyond that, past the grey trunks of the high trees which shade the patio, over a brick fence, which was not solid but composed of as much space as brick, there is the plaza in front of the the Chemin de fer, Dakar au Niger railroad station build in 1924, an almost invisible plaque high on the building told us. Groups of men mingle and converse, and at the edges of this plaza are the peddlar stands where Unité and Liberté, the two national brands of cigarettes, are sold à l’unité but also by the packet.

Evening in Bamako. The terrace and the courtyard, the practically leafless trees etched in the moonlight, offered a friendly world of silver shadows. The moon was full. The air had so rapidly chilled from the afternoon heat that a light breeze raised shivers. Across the courtyard and behind the brick grill which surrounded it, an open air movie blasted reverberating French and rifle shots of a dubbed Western. Broken phrases of a popular song drifted in from another direction and the railroad creaked continuously behind the hotel.

17 January, 1968. The previous day was devoted to travel hassles. We got up the next morning early, checked out and left for Mopti. We left Bamako in a hand-crank-started station wagon and rode through the dry savanna towards Mopti. Bamako is circled by long red cliffs. For a few miles we passed boulders stacked and crumbling in heaps. Then the countryside flattened out and the road straightened and the landscape of knarled baobab trees became monotonous.

The stunted and sun-warped trees, the grey patches of exposed earth, the interminable barrenness of the land was broken only by mud-walled communities which seemed to have either grown out of the soil or been eroded down to it from hills of clay. The villages were long and low and clung to the earth. Over the village conical roofs stuck out in random clusters. Herds of emaciated cattle sometimes blocked the road as they emerged from the bush, and the driver slowed and honked and dodged through them before he regained speed. We just missed a kid goat which dashed across our path as we came around a bend. Later in the afternoon Louis and Tom saw three monkeys, but I was asleep, lulled by the regular rumble of the motor and unchanging format of the scenery.

Just before Ségou we saw the Niger, which swept out to the left in a graceful swampy curve. There were reeds in the water and woman and children washed on the banks or floated near shore on thin barks wavering in the eddies. At the plaza in Ségou we stopped and ate and changed taxis, waited in the hot dust surrounded by small boys peddling sheets of paper and green oranges. Our new driver took fifteen minutes to get out of town and stopped to see every friend he could find, shouting greetings and comments probably curses in Malinké to every man, child and especially woman that he saw. The road was being improved and in the afternoon we chugged through miles of dusty and improvised detours. But I dozed off again, wedged in the back corner between the window and a grey-bearded official carrying his son and wearing a heavy wool uniform. By the time we arrived in San it was too late to continue to Mopti. Night fell quickly and we had hardly found rooms in a nearby resthouse when they started lighting the kerosense lanterns.

We had a good meal of roast chicken and potatoes and salad and strong black coffee then read for an hour or so before turning in and lowering the mosquito nets around our soft, straw-stuffed beds.

19 January, 1968. Just as I was falling to sleep, Louie came knocking at my door to translate. A man offered to take us in his truck to Mopti. We hesitated for a moment but decided to make sure we got to Mopti in time for the boat to Timbuktu, and so decided to take up his offer. About 9 pm we piled into the back of a huge truck full of Malians, bunched togther under woolen blankets and tarpaulins. As the truck moved out into the night, it became colder and colder. The moon was full, covered with a thick haze, and the men joked and laughed until late at night. I had a déjà-vu of incredible proportions and drowsily dreamed of plots and characters for my as-yet conceived novel. But the wind and the chilling air rapidly took any adventure out of the affair. By 3 am, when we finally arrived in Mopti, aching and trembling with cold and muscle cramps, the only hotel had no room and we were forced to sleep on the cold pavement of its terrace surroundbed by swarms of mosquitos.

Before we found that hotel we had walked around town in search of a one. The streets were deserted and dimly lit with street lights distinctly spaced in the night. There was no sound except our footsteps, our half-hearted jests and the whimpers of children crying in the night. I tried to ask directions several times from the occasional passing man or woman wrapped up against the cold, but they turned from me, without answering, as if I were a ghost in the night. Dogs barked and the thin shadows of the pirogues lay slicing into the black mirror of the surrounding swamps.

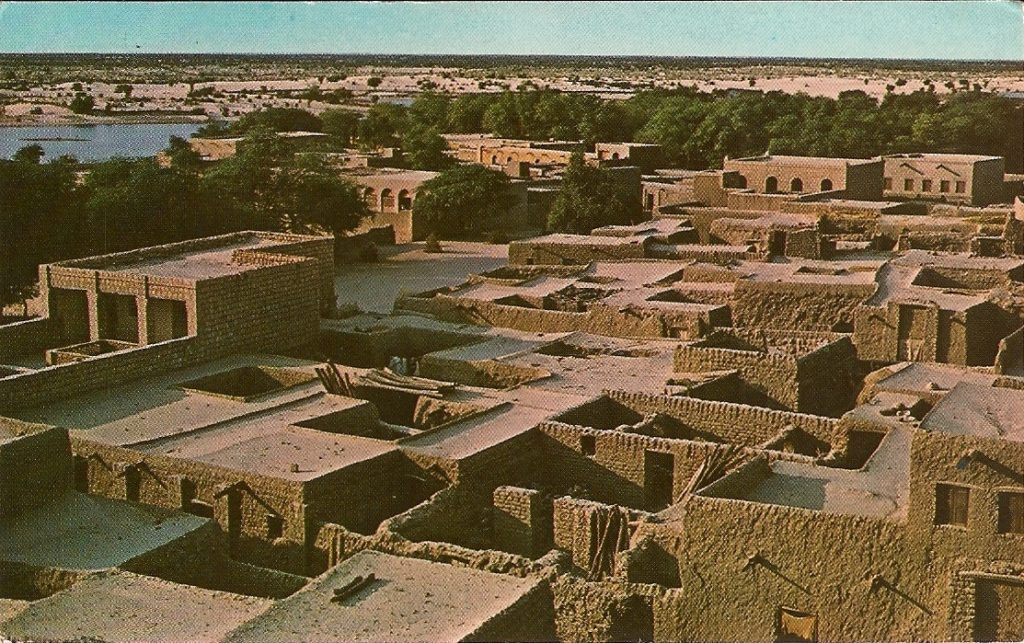

Mopti by day does distantly ressemble Venice, at least geographically, as is claimed by the Tourist Office, because it is built on, indeed seemed to float on brackish water. Low reeds extend as far as the eye can see. One side of town is built around a lagoon, while on the other side of the town the boats line the quais along the river. The main part of the town is composed of a network of streets crossing at right angles through mudbrick and cubical houses. Concrete trenches border all the sides and these are full of refuse and excrement and urine. The smell of these ditches fills the air. Beggars are everywhere, intoning their chants for alms. Young full-breasted girls carry baskets and tubs laden with fruit and vegetables on their heads.

La Liberté, the riverboat to Timbuktu and on to Gao, was scheduled to leave in the late afternoon. Sitting on the deck waiting for the departure we talked with two Peace Corps volonteers from Togo, while surreptitiously watching adolescent girls bathing a hundred yards away. They soaped themselves thoroughly berfore rinsing, maintaining their this waistcloths until the end when they modestly slipped off the wet piece of cloth and quickly wrapped themselves in another.

The passengers were a motley crew. There was an American missionary from Niafounké who had been there ten years and was obnoxiously well-informed. The Yugoslav ambassador from Dakar and his wife and the Dutch ambassador were both aboard, on route to hunt wild game together in the Sahel. The Dutchman had been in a Japanese prison camp for three and a half years. There were also three Frenchmen who had been in Dahomey working in a hospital for their military service, plus three Russians who were part of the Soviet mission to Bamako. I talked for a while with the missionary to try and see what kind of man he would have to be to come here to convert, but he described himself solely in terms of God’s Will, praising the Lord, rationalizations for obsessions of one kind or another familiar enough to me. He did however speak good Malinké.

The Niger is quite broad until Timbuktu and at times you cannot see the distant other shore. There are rarely distinct banks, the river merging unbounded into swamps and watery low-lands. What land you can see becomes more and more sandy and less and less covered with brush until, around Timbuktu, where there is nothing but sand.

The course of the Niger had altered over the years, so the town itself was seven kilometers from the banks at which La Liberté moored, and a group of us hired a truck to take on there for the obligatory sight-seeing. There is however not much to say about Timbuktu, its mosque being the main or maybe only attraction, with the exception of the Post Office, to which we hurried in order to send post cards stamped Timbuktu. Here is one I sent to myself and later retrieved.

We were almost stranded when the driver failed to return for us as he promised, but Yugoslav ambassador somehow wrangled a ride for us in the back of a small covered pick-up, and we rushed back to the port to just catch the boat, which for once seemed to be leaving on schedule.

Late at night and early in the morning the cold was sharp and cut to the marrow. In the afternoon, heat became intense and the sun burnt, cracking your face and lips. There was nothing do on the boat except read and talk and we passed hours on the decks watching the swamps drift by.

20 January, 1968. Last night there were millions of stars until the moon rose and we docked at a small village situated between two dunes which humped up silvery against the sky. Campfires were glimmering in the darkness. As the boat made a slow turn into the shore we saw a crowd of shrouded and turbaned men waiting around a kerosine lantern. Knarled trees veiled the moon. Pirogues swarmed around our boat, loaded with firewood and bundles of pots and pans.

The next morning we passed through the Defile, a narrow gorge between cliffs. Our boat slid through a channel of basalt boulders. Dunes were prevalent and we were truly in the desert, one whose red cliffs and baked outcrops reminded me of the US Southwest.

25 January, 1968. In Gao. Five days have now gone by without entries in my diary. A very taxing five days. We slept on the boat Saturday night, for free it turned out, and then we went to a local hotel for coffee. Afterwards, we walked about a mile to the place where taxies leave for Niamey, and waited for an hour until discover that a rapide would leave that afternoon at 4 pm. We went back to the hotel and ….

*

… There are no more notes, but subsequent events — the forty-eight hour ordeal of the rapide trip to Niamey, the two days there, the flight to Ouagadougou in then Upper Volta, now Burkina Faso, the train down to Abidjan, finally the overland return to Liberia — were etched without words in our three memories, which Louis and Tom and I had a chance to confirm and to render collective 41 years later in California during the reunion we three and the others who were with us at Cuttington College had in 1969. We were lucky to have lived this, and to have lived so long to recall it across our nearly full lifetimes.