[I’m reposting this ten year old piece which has become oddly relevant again ….]

I had been meaning to start as follows:

Years ago on what seems another planet and likely one of the first times I was allowed to take our family car out alone, I drove over to the near north side of Houston to the Al-Ray Theater and saw Black Orpheus. The trailer here is in French, which I was starting to understand, though the film was in a language I had neverf heard before, Portuguese, which continues to feel like I should always have spoken it. This was before the Al-Ray went porn, slipping, back in the Golden Age of Houston cinema palaces, from “Fellini to Deep Throat,” as a 1975 piece in the Texas Monthly put it (p. 72). At that point in time Houston was already the seventh largest American city with more or less a million within its legal limits, and burgeoning. I have long given up trying to explain that, coming from Houston, I didn’t exactly come from nowhere.

Before major U.S. distributors began to pick up and monopolize prize-winning foreign films, which thereafter became unaffordable to Al and Ray, the two entrepreneurial brothers who ran the neighborhood movie-house, the Al-Ray was the premier venue for a slew of foreign films. I saw, many at the tender age of eighteen, parsing out and tentatively pronouncing their titles in French and Italian: Les 400 coups, À bout de souffle, Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (where I probably heard Miles Davis for the first time), La dolce vita, L’avventura, Rocco e i suoi fratelli . The last one starred that sex-god, Alain Delon, whom I imagined I resembled, and was so assured by a less-than-objective potential male lover who did not, however, score. Here I want to tell how in a single evening Black Orpheus decisively shaped who I have become.

I can’t claim I would never have taken up classical guitar without having seen Black Orpheus and then bought the LP, one of the first I owned. There was a guitar in the house, Dad played, so it was perhaps natural that I ended up getting one and taking it to Africa in 1967, this at the same time I began studying Portuguese and where I met my friend Alfredo Pons, a Peace Corps volunteer who played a number of amazing bossa pieces. From the beginning, my guitar repertoire, such as it is, always included the Brazilians, starting with Villa-Lobos. Just this morning I was playing Baden-Powell, his Retrato brasileiro (Brazilian Portrait) and Valsa sem nome (No-name Waltz). Over and over I have returned to the music of that period and, in 2000, I published the article which must now stand as my definitive study of the poetry conveyed therein: Cannibalizing Bossa Nova. A few years later, I had practically set out on a study-tour to Brazil and Venezuela with my guitar on my back in search of the spirit of Bossa Nova, as some overwrought staff writer for University of Alberta Folio put it. Alas, that plan was scotched by my appointment as Dean at Ottawa in 2004. It might yet be revived.

This just scratches the (musical) surface. First and foremost, I had never seen and would not for several more years see a film whose cast was black, let alone one whose lead actress was as captivating as Marpessa Dawn, actually born, I learned much later, in Pittsburgh, and part Filipina, though she performed in Portuguese and was considered a French actress. Things are almost always more complicated than we believe.

I am familiar with academic theories of race and sex, sexualized race, racialized sex, so I know perfectly well Marpessa Dawn was preceded in my psyche by many other black female figures of illicit lust. Her demure beauty nonetheless opened avenues of desire and a mode of yearning I had never conceived of before ….

*

I was going to write all that and more, but then, Googling for clips, I discovered that Barack Obama had already addressed the topic in Dreams from My Father. Having merely leafed through his book, I had missed this reference, one well-discussed, I now know, on the internet and which links me not to him — he is young enough to be my son — but to his mother, a woman only three years older than I and with whom I have a strange generational and cultural affinity.

Here is the passage in which Obama describes his reaction to seeing his mother watch what was the first foreign film she had ever seen:

One evening, while thumbing through The Village Voice, my mother’s eyes lit on an advertisement for a movie, Black Orpheus, that was showing downtown. My mother insisted that we go see it that night; she said that it was the first foreign film she had ever seen.

“I was only sixteen then,” she told us as we entered the elevator. “I’d just been accepted to the University of Chicago – Gramps hadn’t told me yet that he wouldn’t let me go – and I was there for the summer, working as an au pair. It was the first time that I’d ever been really on my own. Gosh, I felt like such an adult. And when I saw this film, I thought it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen.”

We took a cab to the revival theater where the movie was playing. The film, a groundbreaker of sorts due to its mostly black, Brazilian cast, had been made in the fifties. The story line was simple: the myth of the ill-fated lovers Orpheus and Eurydice set in the favelas of Rio during Carnival. In Technicolor splendor, set against scenic green hills, the black and brown Brazilians sang and danced and strummed guitars like carefree birds in colorful plumage. About halfway through the movie, I decided that I’d seen enough, and turned to my mother to see if she might be ready to go. But her face, lit by the blue glow of the screen, was set in a wistful gaze. At that moment, I felt as if I were being given a window into her heart, the unreflective heart of her youth. I suddenly realized that the depiction of childlike blacks I was now seeing on the screen, the reverse image of Conrad’s dark savages, was what my mother had carried with her to Hawaii all those years before, a reflection of the simple fantasies that had been forbidden to a white middle-class girl from Kansas, the promise of another life: warm, sensual, exotic, different.

I turned away, embarrassed for her, irritated with the people around me.

(Dreams from My Father, p. 123 ff)

*

I would stand guilty of similar naïveté if accused but, as Obama knew somewhere, he would not have come onto this planet without the desire this film raised in his mother. Obama’s own dreams are from his father, but hers were of the man. And, lest we forget, his father had his own dreams of her and Obama’s paternal grandfather was absolutely opposed to having “the Obama blood sullied by a white woman” (p. 126).

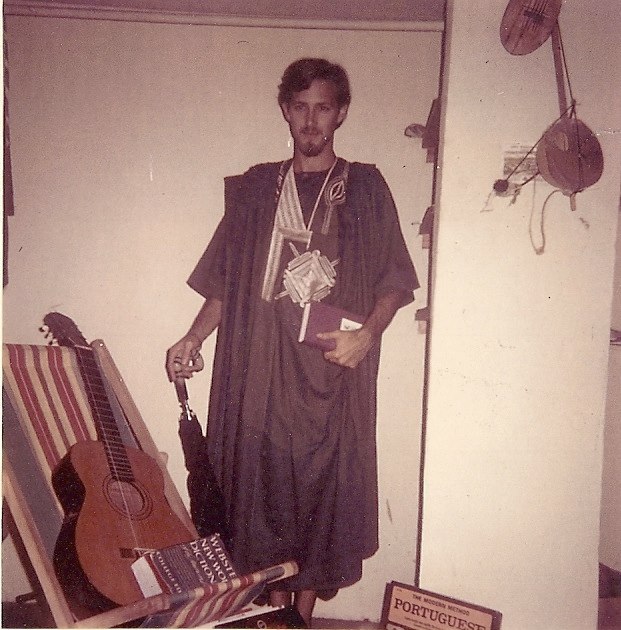

As for myself, I suspect that without Black Orpheus I would never have shored up in West Africa, guitar by my side and – look down in the lower right-hand corner — my Portuguese language-learning set of LPs at my feet.

This photo was deliberately staged, intended to convey several points to the folks back home, for example, those tokens of poetry: the dictionary on the folding chair and the volume of Rimbaud in my hand – Rimbaud, who notoriously abandonned poetry at age twenty and later spent his last years in Africa, a subliminal threat I did not keep.

Framing the miniature kora on the wall across from my guitar made both implicitly interchangeable and hence equal. And, yes, the robe, which I still possess, is gorgeous. Wearing the clothes of “Others” is not an expression of deviant exoticism, rather of acceptance of them, willingness to share bodily sensations, as it were. There is no embrace more intimate except the one without clothes.

The pathways to understanding others are obscure, unpredictable, fraught with inauthenticity. If we remain totally and exclusively authentic to our selves as we have already defined them, will we ever be able to learn or to change?

Without Black Orpheus, I would probably never would then have gone on to commit to the study and promotion of African and Brazilian and Afro-Caribbean literature (in for example, Entwisted Tongues), plus twenty-five years of involvement in and service to the African Literature Association and its French counterpart, A.P.E.L.A. Without Black Orpheus, I would never have been able to owe Africa as much as I do, just as Brazil does – and I shall spare you, for now, my comments on how much the U.S. and in particular the South owes Africa, and I am not talking about reparations.

But when, at the end of the film, the next young Orpheus-to-be himself makes the sun rise over Rio by playing Manhã de carnaval, a piece he had learned from the departed Orpheus, the hidden message is not that blacks are child-like with an inborn gift for dancing (Obama notwithstanding), instead that the mythic cycle of desire and loss always begins anew, desire and loss coming garbed in as many guises as there are peoples in world.

I am lucky to have seen Black Orpheus as a impressionable young adult. Obama is lucky his mother did.