Consider this a drill, an exercise, not live fire.

Xu Zhimo was a “free-thinking Chinese poet who strove to loosen Chinese poetry from its traditional forms, and to reshape it under the influences of Western poetry and the vernacular Chinese language”. Xu’s Adieu to Cambridge 再别康桥 Zài bié kāngqián is far and away his most famous and anthologized poem, written after a stint studying literature in Cambridge in the twenties.

There is an additional topical element to the title and poem. As Brexit proceeds, it does feel to Europeans and EU-philes like myself that the elegiac tone of Adieu to Cambridge has now an inadvertent contemporary overtone.

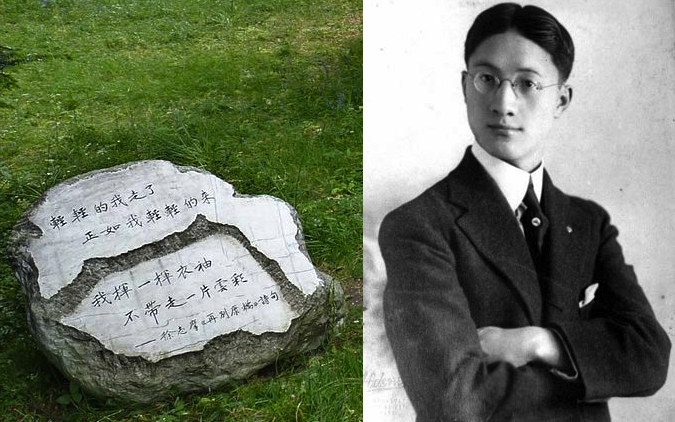

There is a stone Memorial to Xu at King’s College inscribed with the first and last lines of the poem (photo below). There is, fittingly, a crack between the beginning and the end.

*

Easily I take my leave

as easily as I have come

and easily now bid adieu

to clouds in the setting sun.

The willows along the river

glow like rows of brides in golden

veils, their shimmer rippling

like waves in my heart.

Rooted in soft mud, waterweeds

float up gracefully in the placid

currents of the River Cam.

Gladly would I waft like them.

That clear water under the elms

is not a pond but a rainbow

tangled in floating pads

which dream of iridescence.

In search of dreams? Take a pole,

punt up to where green is greenest

in a skiff whose hull is full of stars

singing out their radiance.

But me, I can’t sing aloud.

Even the crickets have fallen silent.

This Cambridge dusk is hushed.

Peace is thus my parting coda.

So quietly I take my leave,

as quietly as I came.

Quietly I shake my sleeves

to leave the clouds behind.

[Mandarin and pinyin follow below. Here is an rhymed translation with comments.]

***

I have occasionally practiced indirect or relay translation of another translation without direct access to the first source language. Most notably, thirty-five years ago in Berkeley a friend took the time to gloss her favorite poems in Russian and then to check my versions against the originals, in search of egregious errors. The most successful is The Yard, my translation of a Osip Mandelstam poem. A few other gloss texts are still in the hamper; another by Nikolai Gumilev provided key phrases and images to Giraffes at San Gorgonio.

Directness is relative. To some extent every translation I have ever made has been mediated by dictionaries, rhyming dictionaries, glossaries and thesauri, even from languages I have some personal control of, starting with English. Degree of indirectness grows inversely per how well we know a language or dialect. For example, the translations of the half dozen or so creoles quoted in Entwisted Tongues: Comparative Creole Literatures, required considerable footwork on my part, since my knowledge of them was bookish. I couldn’t rely on an inner ear.

Having a living interlocutor like my Russian friend is more direct than what I offer here, a translation from twentieth-century Mandarin, a classic known to any literate Chinese reader.

I have smatterings of Mandarin which go back to the summer of 1979, when I suffered a ten-week immersion under the guidance of a Maoist instructor at UC-Berkeley, who memorably informed me that I’d never be able to learn writing let alone proper calligraphy because I am left-handed. Nonetheless, I learned enough Mandarin to avail myself of the wonderous tools the internet provides. My principal interlocutor in this poem has been Google Translate, but I also checked against prior translations, in particular those by Nicole Chiang in her edition of Xu Zhimo’s Selected Poems (Oleander Press), by Cyril Birch (Anthology of Chinese Literature, Vol 2, Grove Press, 1972, pp. 247-48), by Yao Liang et al (in Wen Lu, Collection of the Most Beautiful Poems by Xu Zhimo, Cam Rivers Publications, 2019) and on the site cited above.

***

輕輕的我走了,

Qīng qīng de wǒ zǒule,

正如我輕輕的來;

zhèngrú wǒ qīng qīng de lái;

我輕輕的招手,

Wǒ qīng qīng de zhāoshǒu

作別西天的雲彩。

zuò bié xītiān de yúncai.

那河畔的金柳,

Nà hépàn de jīn liǔ,

是夕陽中的新娘;

shì xīyáng zhōng de xīnniáng;

波光裡的艷影,

Bōguāng lǐ de yàn yǐng

在我的心頭蕩漾。

zài wǒ de xīntóu dàngyàng.

軟泥上的k,

Ruǎnní shàng de qīng xìng,

油油地在水底招搖;

yóu yóu dì zài shuǐdǐ zhāoyáo;

在康河的柔波裡,

Zài kāng hé de róu bō lǐ,

我甘心做一條水草!

wǒ gānxīn zuò yītiáo shuǐcǎo.

那榆蔭下的一潭,

Nà yú yīn xià de yī tá

不是清泉,是天上虹;

Bùshì qīngquán, shì tiānshàng hóng;

揉碎在浮藻間,

Róu suì zài fúzǎo jiān

沉澱著彩虹似的夢。

Chéndiànzhe cǎihóng shì de mèng

尋夢?撐一支長篙,

Xún mèng? Chēng yī zhī zhǎng gāo,

向青草更青處漫溯;

xiàng qīngcǎo gèng qīng chù màn sù;

滿載一船星輝,

Mǎn zǎi yī chuán xīng huī,

在星輝斑斕裡放歌。

zài xīng huī bānlán lǐ fànggē.

但我不能放歌

Dàn wǒ bùnéng fànggē,

悄悄是別離的笙簫;

Qiāoqiāo shì biélí de shēng xiāo;

夏蟲也為我沉默,

Xià chóng yě wèi wǒ chénmò

沉默是今晚的康橋!

Chénmò shì jīn wǎn de kāngqiáo

悄悄的我走了,

Qiāoqiāo de wǒ zǒule

正如我悄悄的來;

Zhèngrú wǒ qiāoqiāo de lái;

我揮一揮衣袖,

Wǒ huī yīhuī yī xiù

不帶走一片雲彩。

Bù dài zǒu yīpiàn yúncai.